- Home

- Neil Beynon

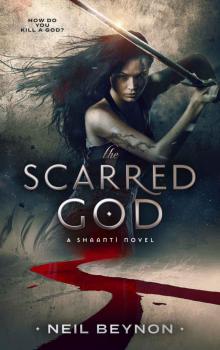

The Scarred God Page 11

The Scarred God Read online

Page 11

They place me on the dais, in the small, shallow dip in the centre. I grow worried as the older man returns with a knife that gleams in the afternoon sun, and the younger man rips open the front of my tunic.

I am different. The world is outside of me. I cannot understand why. The older man speaks softly as he traces the point of the blade down my flat chest. He booms out words I can’t translate as he draws back the knife and swings as if he intends to impale me upon it. He stops. Just short of stabbing me through the chest, close enough to draw blood but not deep enough to slice bone or sinew.

My host lets out a breath I was not aware was being held. The older man places the knife back in his belt and claps. The younger man seems to express disbelief as he leads me out the back of the dais into cooler chambers beyond, my torn tunic flapping in the draught.

This part of the building is darker than the rest, and I enter a room filled with beds. The younger man leads me to a bed near the room’s only window. His words are short but not unkind as he points to a neatly folded, fresh white tunic that sits on the bed. I say nothing but nod when expected, waiting for the man to take his leave, and soon he does. I lie down on the bed. My eyes close.

The presence woke Anya first.

The creature was underneath her. She could feel the beast on the edge of her dream. It darted round, tumbled this way and that, flicking from one side of her to the other, like an eel formed of magic. As she became fully aware of the creature, the thing darted away to somewhere near Pan, and as the god stirred, she felt the energy leap further to Vedic.

‘What is it?’ she hissed at Pan.

The god shook his head. He did not know.

Vedic nipped up from his prone position with his axe in hand.

‘What in Golgotha?’

The figure stood on the edge of the shadows just outside the cave, where the firelight faded. They were hooded in a grey cowl, neither their hands nor face were visible. The person was somewhere between Vedic’s and Cernubus’s height.

The figure spoke in a sibilant tone of indeterminate gender. ‘This place is forbidden.’

‘Morrigan,’ hissed Vedic.

‘No,’ said Pan, raising his hand to stay the woodsman. He stood and moved out of the cave as close as he dared to the figure. ‘I would know if it were her.’

‘You cannot harm me,’ said the creature to Vedic. ‘I died when your kind were still in the trees.’

The figure turned to Pan.

‘But you should know. There are protocols.’

Pan frowned. ‘I know that our need was dire, and no other option had a chance.’

‘You have erred. Things are breaking down as the alignment approaches. You must leave or all is lost.’

‘The scarred one of my kind, the scarred god, he is coming for us.’

‘That is why you must go.’

Pan turned to respond.

‘Leave!’ commanded the figure, and lightning broke from the ground and connected with Pan.

The god fell, skin smoking, and did not move. Vedic jumped for the stranger, but his axe swung through thin air. Anya went to Pan. The trickster had rolled onto his back and was drawing in deep lungfuls of air, staring at the blank black sky.

‘Why are you always right?’ asked the god.

‘Because I pay attention,’ said Vedic. ‘You take your mind for granted.’

Anya could feel the presence below them. It darted and flicked around as if it were – worm-like – swimming through the earth.

‘We are in trouble,’ said Pan, pulling himself to his feet.

‘I told you this was a bad idea,’ hissed Vedic.

‘Yes,’ said Anya, her irritation showing. ‘We’re both very impressed with your prescient insight. Can we get across the valley before—?’

The ground shook, dropping Anya and Vedic to their knees. Pan tilted his head as if listening. The dark made it hard to see, but there was a noise like the grinding of rock on rock, and the shadows appeared to be unfolding from the sides of the hill, growing taller and taller.

‘What in the goddess …?’ breathed Vedic.

‘The statues,’ said Anya, her throat feeling dry and craggy like the mountain. ‘The statues are coming alive.’

Pan gestured straight up the mountainside they were on.

‘We must get back over the ridge.’

The first boulder struck the ground very close to the god and with enough force to throw him several yards. He lay there for a second before rolling to his feet. Vedic was already dragging Anya, without the few supplies and weapons they had, up the mountainside.

‘Our packs!’

Vedic hissed in her ear. ‘Rule one: survive …’

Pan turned from them, his hands glowing as he faced the emerging statues. The sky rained stone and wood as the things lurched and grabbed at whatever they could. The western statue, clutching its baton, was in striking distance and swung down to hit Pan. The god let loose his power by bringing his hands together, and a red beam of light flew from them, striking the statue in its back. The impact shook the whole valley.

Anya looked back at Pan, but the god was on his knees. ‘He’s going to get killed.’

Vedic shook his head. ‘A little gnawed on, perhaps, but they can’t kill him.’

‘What good would he be to us then?’

Vedic frowned. He clearly didn’t want to concede the point, but behind everything was the realisation that he would have to face Cernubus eventually. Anya wondered what hold Danu had on him that he would even think of it. Unbidden, the image of children’s hands reaching for her from the dark rose up. Wait, she told herself, I am coming for you.

‘Wait here,’ he said.

The other statue jumped across the fissure at the foot of the valley, fist raised. The creature brought the hand down so fast there was a sound like a screaming wraith as it drilled into the ground where Pan knelt. The force of the impact sent Anya onto her back. She rolled in the mud and looked up.

The relief of seeing Pan and Vedic sprawled in the dirt a few feet from the statue’s fist was short-lived. As the creature turned to seek Pan, the god shoved the woodsman away as the foot of the statue came down towards them.

The foot stopped about two feet above Pan, cracking against a shield that the god had hastily pulled up but driving him to his knees once more. They stayed like that for a moment, locked against each other. Then Pan began, sweat pouring down him, to stand once more. He shoved up with his hands, and the statue flew up into the air as if hit with an uppercut. The figure landed across the other side of the fissure. A leg draped over the edge.

Pan collapsed.

Vedic grabbed Pan and hoisted him up over his shoulders. Clutching the god’s wrist against his leg with one hand and his axe with the other, he ran past Anya.

‘Follow me,’ he said. ‘They will be back.’

Anya hesitated for a moment, looking back at her makeshift weapon and the blankets that had been discarded. In the distance, she could see the prone statues twitching, and the presence that had woken her was not far away. There was no time. She ran after the forestal as he raced to make the top of the valley.

Near the top, the ground shook once more, and they were spilled onto the rock.

‘What now?’ asked Pan, wearily.

Anya peered through the grey light of dawn. The fissure in the valley’s floor was like a black, malevolent mouth, a smear of shadow darker than everything else. The blackness was moving and extending out onto the solid ground all around. A third statue unfurled with a metallic grinding noise until a hand was clasping onto the rock hard enough to hear the sound of crushing stone.

‘There are more of them,’ she whispered.

Vedic was already on his feet, dragging Pan further up the mountain with him. Anya did not need his encouragement to move again as rocks started landing all around them, thrown by the three statues as they moved up the slope after them. The top of the valley was still being battered by high winds

, and they were almost crawling as they reached the peak. The weather was clearer than earlier: there was no rain, and the coming sunrise was painted on the horizon. The forest stretched out before them, seeming so much bigger than it did on maps that Anya had seen her grandfather pore over in the time before his drinking really got out of hand. Anya let herself hope for a moment that they would get to Danu easily.

‘There you are, little cousin.’

Anya felt her heart stop. She looked across the ridge, three peaks over, at the unmistakable human form of Cernubus standing in shadow, looking over at them, surrounded by the full pack of wolves. Vedic moved between Anya, Pan and the enemy. He did not flinch or show any sign of fear as he raised his axe.

‘No, forestal,’ said Pan, pushing himself to his feet and limping forward. ‘You cannot win this fight. I must face him.’

Vedic looked at him. ‘But you cannot win. You already told me that. At least Danu thought I had a chance.’

‘Not like this,’ said Pan. ‘You will fall if you try, and then what will become of Anya?’

Vedic looked over at her. She wasn’t convinced he cared either way, and she was damned sure she didn’t like feeling that she needed rescuing.

‘I …’

‘Danu said both of you,’ said Pan, softly.

‘What about the Tream?’

Pan smiled sadly. ‘You said it yourself, they may not even notice you’re there. If you do see the Tream and he is amongst them …’

Vedic held the god’s gaze for a moment. ‘I will tell Akyar.’

Pan nodded.

Cernubus and his hunting party had swept to the second peak now. The tattoos on his upper body were visible in the sunrise, writhing like snakes across his skin.

Pan flicked his wrists, and power surged into his hands, purple in the right and red in the left.

‘Do you intend to show me some fireworks, little cousin?’ asked Cernubus, laughing.

Anya shook her head as Vedic approached her. ‘We can’t just leave him.’

Vedic grabbed her arm. ‘We have no choice – let his sacrifice have meaning. If we are still here when the wolves hit this side, we will die.’

Anya’s last glimpse of Pan was as the god was beginning to weave a bigger shield than last time, the side of the hill still shaking as the statues climbed up the inside of the valley. Was he going to …?

Vedic pushed her down into the treeline. They were running for their lives when the top of the mountain exploded and the world became light.

Chapter Eleven

‘How long have we known each other?’

Jeb did not answer. He lifted his right eyebrow in a gesture as familiar to the thain as her own face. She remembered being given that look during her very first lesson on tactics from the only-five-years-older-than-her Jeb. Her mother had been adamant that he was the best mind in the clans to teach her to use her head before she learned to use her blade. She had been only twelve at the time. That felt like a hundred years ago. She heard her mother’s voice, wry amusement in every word, pointing out it actually was nearly a century ago.

‘I’ll remind you,’ she forced herself to continue. ‘A very long time. I hope in that time you have built up trust in me.’

They were in her chambers. Bene was outside the door for security and for the sake of propriety, given Golan’s propensity to use any little infraction of protocol to his own advantage. The thain was standing by her burning fire, warming her bones and sipping wine, while Jeb was sitting on the spare chair she kept for the odd audience she granted to her subjects.

‘Milady knows I am ever her servant,’ said Jeb.

Did she imagine the tone in his voice? A contradiction unspoken …

‘What is on your mind, old friend?’ she asked.

Jeb sighed. ‘I have never been able to hide anything from you.’

‘Why would you?’ she asked, her voice hurt. If she could not trust Jeb, her oldest confidant, she was alone.

Jeb looked round, as if seeking an escape tunnel. There was no way to avoid his old friend. He had been asked a direct question by his thain, and he must answer.

‘One of my people saw a shadow leave your room,’ he said.

It was an old fight. Jeb had kept the secret for so long they rarely spoke of the shadow any more, but he had broken that unspoken détente.

‘That is not your concern,’ she whispered. ‘My people must bring me the information I seek when the council doesn’t operate for the defence of our realm.’

Jeb nodded. ‘This shadow stayed a long time. Was there much intelligence?’

The thain glared at him.

He raised his arms in surrender. You asked …

‘I must send you on one last mission,’ she said.

Jeb blinked.

‘What is that?’

The thain looked away from him. She was ashamed. She was going to send this man who was so near the end of his life he barely left the city walls at all on a journey that might kill him, even if he did succeed.

‘I need you to go to the forest.’

Jeb stared at her like she had gone mad. ‘Even if I got there, what do you hope to achieve?’

‘You have your people in the city,’ said the thain. ‘Mine roam far and wide, bringing me intelligence of what they have seen, and our borders are collapsing. In order to survive, we need the forest and at the very least the safe passage that only the gods can bestow. Of those of us granted leave to enter, you and I are the only surviving members now Falkirk has died. I cannot leave. I must send you.’

Jeb poked at the fire with his stick. He looked as if he were stoking the flames against the journey to come.

‘Of course,’ he said. ‘I will go, but I am unsure if I will return, even if she agrees.’

‘I know,’ said the thain. She felt as though she were three hundred years old.

‘What do you think will happen? Will they help us?’

The thain shrugged. ‘Who knows where the gods are concerned? I never fathomed Danu’s reasons when we used to see her every day. That was a long time ago.’

‘Golan will never accept the assistance of the gods,’ said Jeb. ‘He thinks we made them up to secure our power base.’

‘Thankfully, Golan does not actually head the council, contrary to what he seems to think – that is still my task. This is our best option.’

The thain’s eyes settled on the small likeness of her son that she had hanging from the wall above her bed. The firelight flickered an orange beast in the reflection of the mirrors in the room.

‘You should never have formed the council,’ said Jeb. ‘It is misplaced guilt that led us here.’

The thain found herself unable to look away from her son’s dark eyes.

‘He was such a beautiful child,’ she said, her voice soft. ‘So gentle.’

Jeb lit his pipe. ‘Too gentle for this world. I am sorry, Robin. I have not stopped being sorry since the day they brought him back.’

‘You haven’t called me that in ten years,’ she said. His old nickname for her dated back to her first lessons with him. She had been a defiant talker when all he wanted was silence.

‘Well, you haven’t needed it in a while,’ he said, a ghost of a smile on his lips.

‘Maybe I did force us down this road too soon,’ said the thain. ‘But not out of guilt. My son saw what we would not. Who power resides with is the toss of the dice, but at least with a council, there is some say, some chance to correct a misthrow.’

‘But only if the person tells the truth. Golan does not.’

‘Yes,’ said the thain. ‘We have arrived at the problem. Not everyone thinks the same, or with the wisdom we have obtained …’

Jeb laughed. ‘You jest with me.’

The thain smiled. ‘Only a little.’

‘Perhaps we should have drawn council members at random.’

The thain frowned. ‘Perhaps. Too late now. We must press on as we are or risk everything. Will

you take the mission?’

Jeb rose from the chair, sucked on his pipe and exhaled.

‘On one condition.’

The thain tilted her head, waiting for the constraint.

‘How sick are you?’

The question drove the air out of her as if he had struck her in the stomach, and she placed one hand out on the mantel to steady herself.

‘How?’

‘The good doctor did not betray you,’ said Jeb. ‘No one knows but me and the person who observed the doctor visiting this wing. I am not sure even they will have drawn the connection. I worked it out myself.’

The thain walked to her chair and sat down. She placed her head in her hands. She could not bring herself to tell him.

Jeb swore. ‘How long do you have?’

‘Stop it.’

‘Stop what?’

‘Reading me like I’m one of your bloody books.’

Jeb shuffled over to her. His walking stick clacked on the stone like a giant insect approaching. He placed a hot, dry hand on her shoulder.

‘I am sorry you felt you had to carry this alone,’ he said. ‘I would … I will keep your secret. But you must not let the council take your place. You must appoint an heir.’

The old man was not telling her anything she did not know. The council were not ready. She had too little time to prepare, and yet she’d had so many years since she made that promise. She looked back up at her son’s image. So long since she had held his head, the life leaving him, even as she had cradled him on the steps of the city like he was still a little boy.

‘We all have the same time,’ she whispered.

Jeb said nothing. He had heard her mother say that when he, too, was young. She knew that much. They had debated the truth of the saying when trekking round the Shaanti with the then thain, dealing with all the petty rivalries that had seemed so important before the Kurah came the first time.

The knock broke the silence.

‘Yes, Bene, what is it?’

The general stepped into the room. ‘Milady, Golan is down by the city wall, questioning the deployment of troops and food reserves.’ The thain could feel Jeb’s temper bubbling without turning.

The Scarred God

The Scarred God